Growing your own fig tree is one of the most rewarding endeavors in home gardening. These ancient trees combine ease of cultivation with generous productivity, thriving in a wide range of climates and requiring minimal care once established. Whether you have a sprawling backyard in California or a small balcony in New York, there’s a way to grow figs. This guide will walk you through everything you need to know to successfully cultivate these remarkable trees.

Understanding your climate and choosing the right approach for growing figs

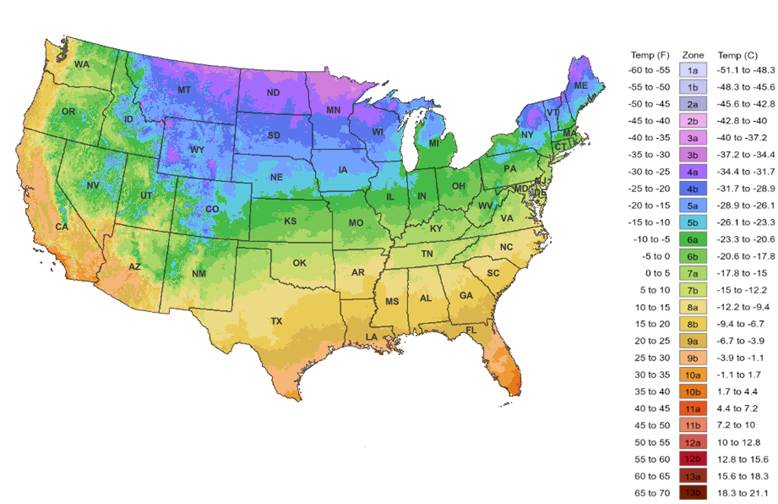

Figs are native to the Mediterranean region and thrive in USDA hardiness zones 7 through 11, though with protection they can survive in zone 6 and even zone 5 with dedicated care. The key to success lies in understanding your climate and adapting your approach accordingly.

In zones 8 through 11, figs can be grown as standard outdoor trees with minimal winter protection. These regions provide the long, warm growing season figs prefer, and winter temperatures rarely threaten the trees’ survival. Southern California, the Gulf Coast, Florida, and the Southwest offer nearly ideal conditions.

Zones 7 and colder zone 8 areas require more strategic planning. Here, figs benefit from sheltered locations near south-facing walls that absorb and radiate heat. The trees may die back to the ground in harsh winters but will regrow from the roots if mulched heavily. In these zones, selecting cold-hardy varieties becomes crucial.

USDA growing zone map.

Zones 5 and 6 present a challenge but not an impossibility. Gardeners in these regions typically pursue one of three strategies: growing figs in containers that can be moved indoors for winter, planting in-ground trees and burying them for winter protection (a technique called “trench planting”), or growing figs in greenhouses or high tunnels.

The amount of heat your location receives matters as much as minimum temperatures. Figs require 100 to 200 frost-free days to ripen fruit, depending on variety. Areas with cool, short summers may see figs form but never fully ripen. If your growing season is marginal, focus on varieties known for early ripening and consider microclimates around your property that might provide extra warmth.

Selecting the right variety of fig

Choosing the appropriate fig variety for your climate and purposes is perhaps the most important decision you’ll make. Common figs, which produce fruit without pollination, are the best choice for most home growers and all cold-climate growers, since fig wasps don’t survive freezing temperatures.

Cold-hardy fig varieties for zones 7 and below

Chicago Hardy (also called Bensonhurst Purple) lives up to its name, surviving temperatures down to -10°F with heavy mulching. It produces medium-sized, mahogany-brown figs with strawberry-red flesh. Even if the top dies back, the roots survive and produce a new tree that bears fruit the same year on new wood.

Brown Turkey is widely adapted and moderately cold hardy, surviving to about 10°F. It produces two crops: a small early crop (breba) on old wood and a larger main crop on new growth. The figs are medium to large with copper-brown skin and pink flesh. This variety’s reliability makes it the most widely planted fig in the United States.

Celeste, sometimes called Sugar Fig or Honey Fig, tolerates cold to about 10°F and produces small to medium, violet-bronze figs with amber flesh that’s exceptionally sweet. The tree stays relatively compact, making it suitable for smaller spaces or container growing.

Fig varieties for warmer climates

Black Mission thrives in zones 8 through 10, producing purple-black figs with pink flesh. This variety is what most people picture when they think of figs, having been grown in California missions since the 1700s. The flavor is rich and complex, excellent fresh or dried.

Kadota is a green-skinned fig with amber flesh, prized for canning and drying. It produces heavily in warm climates but won’t ripen in cool-summer regions. The flavor is milder and less sweet than dark varieties.

Desert King excels in maritime climates and produces large, green figs with strawberry-colored flesh. Interestingly, it produces better in cooler summers than hot ones, making it perfect for the Pacific Northwest.

Site selection and soil preparation for figs

Figs are remarkably tolerant of soil conditions but perform best with proper site selection. Choose the warmest spot available on your property. South-facing locations near buildings or walls benefit from reflected heat and protection from cold winds. In hot desert climates, afternoon shade prevents fruit from scorching.

Drainage is more critical than soil fertility. Figs tolerate poor, rocky soil but will not survive in waterlogged conditions. If your soil is heavy clay, consider planting on a mound or berm to improve drainage. Sandy soils pose fewer problems, though you’ll need to water more frequently.

Soil pH between 6.0 and 6.5 is ideal, but figs adapt to slightly alkaline conditions as well. If you’re unsure about your soil, a simple test kit from your local extension office will provide guidance. Most soils require no amendment, but if your soil is extremely poor, working in compost before planting improves initial establishment.

Space is another consideration. Standard fig trees can reach 15 to 30 feet tall and equally wide, though most gardeners keep them pruned smaller. Allow at least 15 to 20 feet between trees for full-size specimens. If space is limited, many varieties naturally stay compact or respond well to pruning, and some can be maintained at 6 to 8 feet tall.

Be mindful of underground utilities and structures. While fig roots aren’t as aggressive as some trees, they spread widely searching for water. Avoid planting directly over septic systems or near foundations in areas where soil shrinks and swells with moisture changes.

Planting your fig tree

The best time to plant depends on your climate. In zones 8 through 11, plant in fall or winter while the tree is dormant, giving roots time to establish before hot weather arrives. In zones 7 and colder, plant in early spring after the last frost, maximizing growing time before the next winter.

Bare-root trees, typically available from mail-order nurseries in late winter, offer the best selection of varieties. They arrive dormant and should be planted immediately or heeled into moist soil or sawdust until planting. Soak the roots in water for a few hours before planting to rehydrate them.

Container-grown trees from nurseries can be planted any time during the growing season but establish most easily in spring. They offer the advantage of immediate visual impact and the ability to see exactly what you’re getting.

To plant, dig a hole two to three times wider than the root ball but only as deep. You want the tree at the same depth it grew previously, or very slightly deeper. Creating a wide planting hole encourages roots to spread into the surrounding soil quickly.

Position the tree in the hole and backfill with the native soil you removed. Don’t add amendments to the backfill in most cases, as this can discourage roots from venturing into the surrounding soil. Firm the soil gently to remove large air pockets, then water thoroughly to settle everything in place.

Create a shallow basin around the tree to hold water during the first growing season. This basin should extend beyond the root zone and helps direct water to developing roots. After a year, you can level it out.

Watering strategies for fig establishment and production

Newly planted figs need consistent moisture to establish a strong root system. Water deeply two to three times per week for the first month, then gradually reduce frequency while increasing the amount of water per session. Deep, infrequent watering encourages deep root growth, making trees more drought-tolerant once established.

By the second year, most fig trees need watering only during dry spells. Established trees are remarkably drought-tolerant thanks to their extensive root systems. However, consistent moisture during fruit development significantly improves fruit size and quality. If rainfall is scarce during the ripening period, water deeply every 7 to 10 days.

Watch for signs of water stress: wilting leaves, yellowing foliage, or fruit that splits or drops prematurely. Conversely, overwatering causes root rot, evident in yellowing leaves that don’t perk up with water, stunted growth, or a general decline in vigor.

Mulching conserves moisture, moderates soil temperature, and suppresses weeds. Apply 3 to 4 inches of organic mulch like wood chips, shredded bark, or straw around the tree, keeping it a few inches away from the trunk to prevent rot. As mulch decomposes, it gradually improves soil structure and provides gentle fertilization.

Fertilization for figs: Less is often more

Figs are famously undemanding regarding fertilization. In fact, overfertilizing causes problems more often than underfertilizing. Excess nitrogen produces lush vegetative growth at the expense of fruit production and can make trees less cold-hardy.

For trees growing in reasonable soil, minimal fertilization is needed. An annual application of compost around the drip line provides sufficient nutrients for most situations. Spread 1 to 2 inches of compost in late winter, and let rain or irrigation carry nutrients down to the roots.

If growth seems slow or leaves appear pale, a light application of balanced fertilizer in early spring may help. Use a formula like 10-10-10 or 8-8-8, applying no more than one pound per year of tree age up to a maximum of 5 to 6 pounds for mature trees. Scatter fertilizer around the drip line, not against the trunk.

Avoid fertilizing after June in cold climates. Late-season fertilization stimulates new growth that won’t harden off before winter, increasing cold damage risk. In warm climates where growth continues year-round, you can apply small amounts of fertilizer in summer if needed.

Yellowing leaves with green veins suggest iron deficiency, common in alkaline soils. Foliar sprays of chelated iron provide quick correction, while sulfur applied to the soil helps long-term by acidifying it slightly.

Fig pruning techniques for different climates

Pruning approaches vary dramatically based on climate. In warm regions where trees never freeze back, pruning focuses on shaping, size control, and maintaining productivity. In cold regions where freeze-back is expected, pruning is less about technique and more about cleanup.

Fig pruning in warm climates (zones 8 through 11)

Prune during winter dormancy, typically January through February. The goals are maintaining manageable size, removing dead or crossing branches, and opening the canopy to light and air circulation.

Start by removing any dead, diseased, or damaged wood. Next, eliminate branches that cross or rub against each other, choosing the better-positioned branch to keep. Remove water sprouts (vigorous vertical shoots) and suckers growing from the base or roots.

Fig trees produce fruit on new growth and sometimes on one-year-old wood (breba crop). Heavy pruning reduces the breba crop but doesn’t affect the main crop. Light to moderate pruning maintains both crops.

To maintain size, cut branches back to a lateral branch, which encourages branching and keeps the tree compact. Heading cuts (cutting partway along a branch) produce vigorous regrowth and should be used sparingly. Most pruning should be thinning cuts that remove entire branches back to their origin.

Some growers maintain figs as large shrubs with multiple trunks rather than single-trunk trees. This approach distributes fruit production across multiple stems and provides backup trunks if one is damaged.

Fig pruning in cold climates (zones 7 and below):

Winter pruning is often unnecessary since nature does it for you. In spring, after new growth begins, remove any dead wood. If the entire top died, cut it back to living tissue or to ground level if necessary.

Don’t be discouraged by freeze-back. Cold-hardy varieties like Chicago Hardy produce fruit on new wood, so trees that die back to the ground can still produce a full crop by late summer. The tree essentially behaves as a herbaceous perennial in these climates.

New growth on fig tree, by Amine Charnoubi, CC-BY-SA 4.0.

Summer pruning controls size and encourages branching. Pinching or cutting shoot tips in June forces lateral branching, creating a bushier plant. This is especially useful for container-grown figs.

Common fig pests and diseases with organic solutions

Figs are relatively pest and disease resistant compared to many fruit trees, but a few problems occur occasionally. Most can be managed without synthetic chemicals.

- Fig rust appears as orange or rust-colored spots on leaves, usually in late summer or fall. It rarely causes serious harm but can defoliate trees in severe cases. Rake and destroy fallen leaves to reduce spore overwintering. Neem oil sprays provide some control, though by the time rust appears, the season is usually nearly over anyway.

- Root-knot nematodes are microscopic roundworms that attack roots, causing galls, stunted growth, and poor fruit production. They’re primarily a problem in sandy soils in warm climates. Resistant rootstocks like VPI provide protection. Planting marigolds around figs and incorporating their residue into soil has shown some suppressive effect.

- Birds are the most common “pest,” competing enthusiastically with gardeners for ripe figs. Netting is the most effective solution, though challenging to apply to large trees. Some gardeners plant extra trees to share with wildlife. Reflective tape, predator decoys, and noisemakers provide temporary deterrence but birds usually adapt.

- Squirrels and raccoons also enjoy figs. Individual fruit protection using organza bags or paper sacks works for small numbers of figs. Hot pepper sprays deter some animals, though persistent individuals learn to tolerate them.

- Fig beetles and dried fruit beetles tunnel into ripening fruit, ruining it. Harvest figs at peak ripeness before beetles attack them. Removing fallen, overripe fruit eliminates breeding sites. Traps baited with fermenting fruit placed away from trees can catch adults.

- Souring is a bacterial infection that causes fruit to smell fermented and develop an unpleasant taste. It’s spread by insects, particularly by vinegar flies entering through the ostiole. Choose whole-fruit varieties with a tight ostiole in humid climates. Prompt harvest of ripe fruit reduces problems.

Winter protection strategies

In marginal climates, winter protection can mean the difference between success and failure. Several techniques help figs survive and produce in challenging climates.

- Heavy mulching is the simplest protection. After the first frost, pile mulch, leaves, or straw 12 to 18 inches deep around the base of the tree, extending several feet out. This insulates roots and the crown, ensuring survival even if the top freezes. Remove excess mulch in spring after the last frost.

- Tree wrapping protects trunks and lower branches from freeze damage. Wrap the trunk and main branches with burlap, frost blankets, or bubble wrap, leaving the top uncovered. Some gardeners create a wire cage around small trees and fill it with leaves for insulation.

- Trench planting is a technique for zones 5 and 6. Plant the fig tree at a 45-degree angle in a trench. In fall, after leaf drop, bend the entire tree down into the trench and cover it with soil and mulch. In spring, uncover it and let it grow upright for the season. This technique requires flexible young trees and becomes impractical as trees age and thicken.

- Covers and temporary structures work for small trees. Cold frames, hoop houses, or even cardboard boxes can protect young trees during unexpected cold snaps. Christmas lights strung through branches add a few degrees of warmth.

In zones 8 and warmer, minimal or no protection is needed. A freeze blanket during unusually cold nights provides insurance for tender new growth in early spring.

Container growing figs for flexibility and cold climates

Growing figs in containers offers tremendous advantages: mobility for winter protection, size control, and the ability to grow figs in unsuitable climates. Many varieties adapt well to container culture.

Potted fig tree at Ivy Cottage, New Cut, Westfield, UK, by Patrick Roper, CC-BY-SA 2.0.

Choose a container at least 15 to 20 gallons for a productive fig tree, larger if possible. Half whiskey barrels work perfectly. Ensure adequate drainage holes, as waterlogged roots quickly kill figs. Terra cotta or wood breathes better than plastic, though plastic retains moisture longer between waterings.

Use a high-quality potting mix, not garden soil. Container mixes drain well while retaining moisture, crucial for container plants that can’t send roots deep in search of water. Mix in some compost for nutrients and beneficial microorganisms.

Container figs require more frequent watering than in-ground trees, sometimes daily in summer heat. Check soil moisture regularly by feeling the top inch of soil. Water thoroughly when the top inch dries out, letting excess drain away.

Fertilize container figs more frequently than in-ground trees, as nutrients leach out with regular watering. Use a balanced liquid fertilizer every two to three weeks during the growing season, or incorporate slow-release fertilizer into the potting mix at planting.

Prune container figs more aggressively to maintain manageable size. Many growers keep container figs at 6 to 8 feet tall through regular pruning and root pruning.

Root pruning every two to three years prevents the tree from becoming root-bound. In late winter, remove the tree from its container, trim away the outer 2 to 3 inches of roots, and repot with fresh soil. This rejuvenates the tree and maintains vigor.

For winter protection, move container figs to an unheated garage, basement, or shed where temperatures stay between 30 and 50°F. The tree will go dormant and lose its leaves. Water sparingly, just enough to keep roots from drying completely. In spring, gradually reintroduce the tree to outdoor conditions over a week or two.

Frequently asked questions about growing figs

Can I grow a fig tree in my climate?

Figs thrive in USDA hardiness zones 7 through 11, but with proper protection they can survive in zones 6 and even zone 5. In zones 8 through 11, you can grow figs as standard outdoor trees with minimal winter protection. In zones 7 and colder, you’ll need to choose cold-hardy varieties and provide winter protection, or grow figs in containers that can be moved indoors. The key factors are not just minimum temperatures but also having 100 to 200 frost-free days for fruit to ripen. If your growing season is short, focus on early-ripening varieties.

What’s the best fig variety for cold climates?

A: Chicago Hardy (also called Bensonhurst Purple) is the champion for cold climates, surviving temperatures down to -10°F with heavy mulching. Even if the top dies back, the roots survive and produce fruit the same year on new wood. Brown Turkey and Celeste are also good choices, both tolerating cold down to about 10°F. All three are common figs that don’t require pollination, which is essential since fig wasps don’t survive freezing temperatures.

Do fig trees need a lot of fertilizer?

No! Figs are famously undemanding when it comes to fertilization. In fact, overfertilizing causes more problems than underfertilizing. Excess nitrogen produces lush foliage at the expense of fruit and can make trees less cold-hardy. For trees in reasonable soil, an annual application of 1 to 2 inches of compost in late winter provides sufficient nutrients. Only fertilize if growth seems slow or leaves appear pale, and avoid fertilizing after June in cold climates.

How often do fig trees need watering?

Newly planted figs need consistent moisture, watering deeply two to three times per week for the first month. By the second year, established trees are remarkably drought-tolerant and need watering only during dry spells. However, consistent moisture during fruit development significantly improves fruit size and quality. If rainfall is scarce during ripening, water deeply every 7 to 10 days. Watch for wilting leaves or fruit that splits as signs of water stress.

Can I grow a fig tree in a container?

Absolutely! Container growing offers tremendous advantages, especially mobility for winter protection and the ability to grow figs in unsuitable climates. Choose a container at least 15 to 20 gallons (half whiskey barrels work perfectly) with adequate drainage holes. Use high-quality potting mix, not garden soil. Container figs need more frequent watering (sometimes daily in summer) and fertilizing than in-ground trees. Prune aggressively to maintain manageable size, typically 6 to 8 feet tall.

Will my fig tree produce fruit if it freezes back to the ground in winter?

Yes, if you’re growing the right variety! Cold-hardy varieties like Chicago Hardy produce fruit on new wood, so trees that die back to the ground can still produce a full crop by late summer. The tree essentially behaves as a herbaceous perennial in cold climates. Heavy mulching (12 to 18 inches deep) around the base ensures the roots and crown survive even if the top freezes.

How do I protect my figs from birds?

Birds are the most common “pest” for fig growers. Netting is the most effective solution, though it’s challenging to apply to large trees. Some gardeners plant extra trees to share with wildlife. Reflective tape, predator decoys, and noisemakers provide temporary deterrence, but birds usually adapt. For small numbers of figs, individual fruit protection using organza bags or paper sacks works well.

Do I need to prune my fig tree?

It depends on your climate. In warm climates (zones 8 through 11), prune during winter dormancy to maintain manageable size, remove dead or crossing branches, and open the canopy for light and air circulation. In cold climates (zones 7 and below), winter pruning is often unnecessary since freeze-back does it for you. In spring, simply remove dead wood after new growth begins. Summer pruning in any climate controls size and encourages branching.

When is the best time to plant a fig tree?

In zones 8 through 11, plant in fall or winter while the tree is dormant, giving roots time to establish before hot weather arrives. In zones 7 and colder, plant in early spring after the last frost to maximize growing time before the next winter. Bare-root trees from mail-order nurseries offer the best variety selection and should be planted in late winter. Container-grown trees can be planted any time during the growing season but establish most easily in spring.

What kind of soil do figs need?

Figs are remarkably tolerant of soil conditions. Drainage is more critical than soil fertility. Figs tolerate poor, rocky soil but will not survive in waterlogged conditions. If you have heavy clay, plant on a mound or berm to improve drainage. Soil pH between 6.0 and 6.5 is ideal, but figs adapt to slightly alkaline conditions. Most soils require no amendment, though working in compost before planting helps with initial establishment if your soil is extremely poor.

What is trench planting and when should I use it?

Trench planting is a technique for zones 5 and 6 where winters are extremely cold. Plant the fig tree at a 45-degree angle in a trench. In fall after leaf drop, bend the entire tree down into the trench and cover it with soil and mulch for winter protection. In spring, uncover it and let it grow upright for the season. This technique requires flexible young trees and becomes impractical as trees age and thicken, but it allows fig growing in climates that would otherwise be impossible.

How long before my fig tree produces fruit?

While the article doesn’t specifically state timing, fig trees typically begin producing within 1 to 2 years of planting, especially common fig varieties. Cold-hardy varieties like Chicago Hardy can produce fruit the same year on new wood, even if they froze back to the ground over winter. Container-grown trees from nurseries may produce fruit in their first season if they’re already mature enough.

Where should I plant my fig tree for the best results?

Choose the warmest spot available on your property. South-facing locations near buildings or walls are ideal because they benefit from reflected heat and protection from cold winds. In hot desert climates, provide afternoon shade to prevent fruit scorching. Ensure good drainage and avoid planting over septic systems or near foundations. Standard fig trees can reach 15 to 30 feet tall and equally wide, so allow at least 15 to 20 feet between trees, though most gardeners keep them pruned smaller.

How do I overwinter a container fig?

Move container figs to an unheated garage, basement, or shed where temperatures stay between 30 and 50°F. The tree will go dormant and lose its leaves naturally. Water sparingly during winter, just enough to keep roots from drying out completely. In spring, gradually reintroduce the tree to outdoor conditions over a week or two to prevent shock. This method allows fig growing in climates far colder than the tree could naturally survive.

Leave a Reply