Few fruits can claim a relationship with humanity as ancient and intertwined as the fig. From the earliest whispers of agriculture to the tables of emperors and the pages of sacred texts, figs have been cultivating civilization just as surely as humans have been cultivating them. This is the story of how a Mediterranean fruit became a symbol of abundance, knowledge, enlightenment, and peace across millennia and continents.

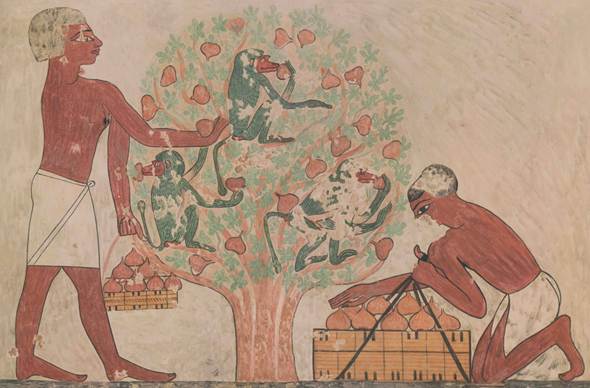

Men gathering figs in an ancient Egyptian painting.

One of humanity’s first crops

In 2006, archaeologists working at Gilgal I, a village site in the Jordan Valley, made a discovery that rewrote agricultural history. They found nine carbonized figs and hundreds of fig fragments dating to approximately 11,400 years ago, roughly a thousand years before the domestication of wheat, barley, and legumes. These weren’t ordinary figs. They were parthenocarpic, meaning they developed without pollination, a trait that doesn’t occur naturally in wild figs. Someone had intentionally propagated these mutant trees.

This discovery suggests that fig cultivation may be the oldest form of agriculture practiced by humans. The process would have been remarkably simple compared to grain cultivation. A farmer who noticed a tree producing seedless figs could propagate it by simply cutting off a branch and planting it in the ground. Fig cuttings root easily, and the clones would produce the same parthenocarpic fruit. No understanding of cross-pollination or seed selection required, just observation and the ability to stick a branch in soil.

Carbonized figs found at the Gilgal I site.

Wild figs (Ficus carica var. sylvestris) still grow throughout the Mediterranean and Middle East, their small, seedy fruits a far cry from the plump, sweet figs we know today. The transformation from wild to domesticated fig happened not through seed selection but through the propagation of mutant trees that didn’t need pollination. This gave early farmers consistent, reliable fruit production without depending on the presence of fig wasps.

Figs in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt

By the time the first cities rose in Mesopotamia, figs were already an established crop. Sumerian tablets from around 2500 BCE mention figs among lists of foods, and they appear in early medical texts as both food and medicine. The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of humanity’s oldest written stories, describes a garden containing fig trees among other sacred plants.

In ancient Egypt, figs achieved an almost sacred status. The sycamore fig (Ficus sycomorus), a related species that produces smaller fruit directly on its trunk, was considered a manifestation of the goddess Hathor, who was sometimes called “Lady of the Sycamore.” Egyptian tomb paintings frequently depict fig harvests, and dried figs were placed in burial chambers to nourish the deceased in the afterlife.

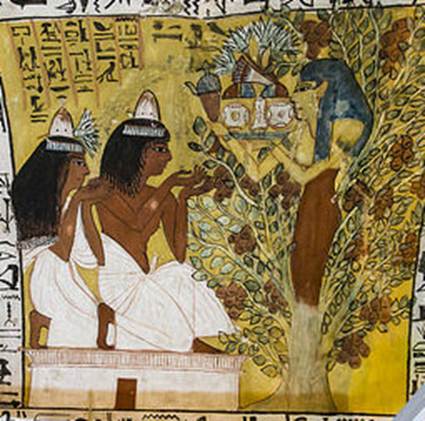

Sennedjem and Iyneferti with The Lady of the Sycamore, by Soutekh67, CC-BY-SA.

The Egyptians developed sophisticated fig cultivation techniques, including a practice called “gashing” where they would wound the young sycamore figs to speed ripening. This unknowingly mimicked the effect of fig wasp activity. Figs were so integral to Egyptian life that the hieroglyph for “fig” also meant “sweet” and appears in numerous contexts throughout ancient Egyptian writing.

Greece and Rome: From Romulus to rhetoric

The ancient Greeks elevated figs from mere sustenance to cultural icon. Figs were sacred to Dionysus, god of wine and ecstasy, and his followers wore wreaths of fig leaves during celebrations. The city of Athens so prized its figs that exporting them was illegal, and informers who reported illegal fig exports were called “sycophants,” a word that combined “sykon” (fig) and “phantes” (to show). This term evolved into our modern word for someone who curries favor through false accusations.

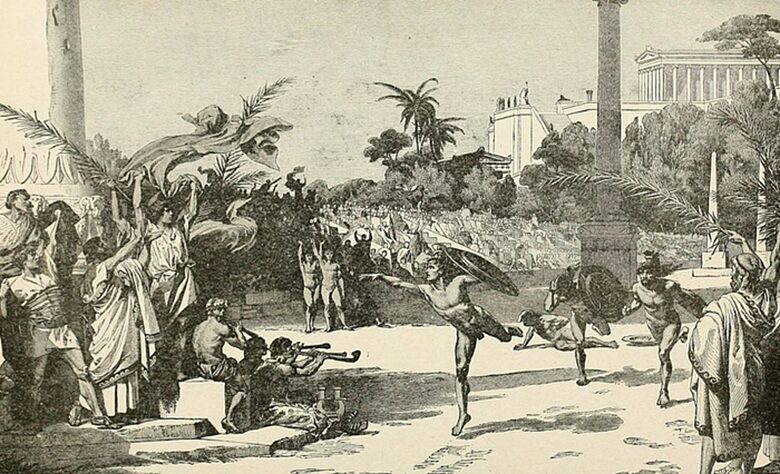

Greek athletes training for the Olympics consumed figs as a primary training food. The physician Galen recommended them for building strength, and Olympic victors were often presented with figs as part of their prize. Plato himself was nicknamed “broad-shouldered” partly because he was said to have eaten many figs, which were believed to promote physical development.

Ancient Greek athletes in the Olympic games.

The Romans took their fig obsession even further. According to legend, the she-wolf that suckled Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome, rested under a fig tree. This tree, the Ficus Ruminalis, became one of Rome’s most sacred sites, and its health was seen as an omen for the city’s fortunes. When the tree died, it was considered a grave portent, and a replacement would be ceremonially planted.

Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder catalogued 29 varieties of figs in his Natural History, describing their characteristics, origins, and uses. He wrote that figs “increase the strength of young people, preserve the elderly in better health, and make them look younger with fewer wrinkles.” The Romans spread fig cultivation throughout their empire, planting trees from Britain to North Africa.

Ancient Roman fresco showing a basket of figs.

Roman politician Cato the Elder famously used figs in a dramatic political gesture. Determined to convince the Senate to destroy Carthage, he ended every speech with “Carthago delenda est” (Carthage must be destroyed) and once produced fresh figs in the Senate chamber. He announced they had been picked in Carthage just three days earlier, demonstrating how dangerously close Rome’s rival was. His campaign succeeded, leading to the Third Punic War.

Figs in religious texts and traditions

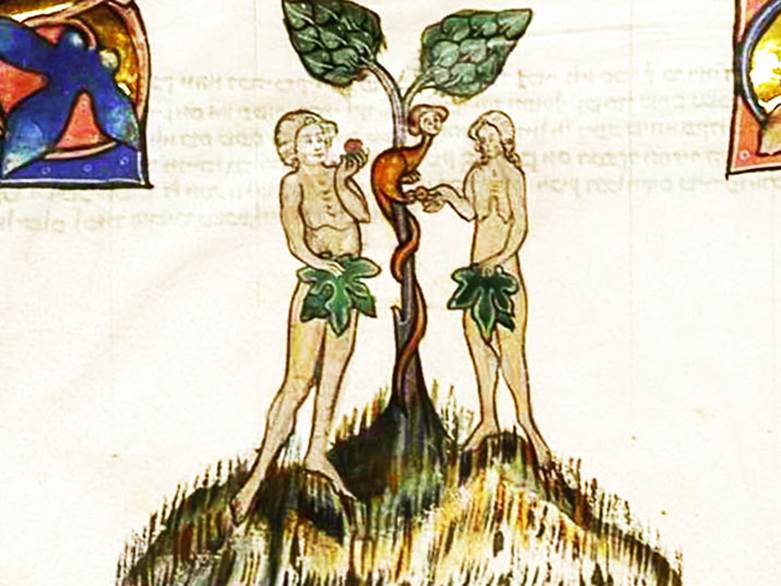

Figs appear throughout sacred texts of multiple traditions, often carrying deep symbolic weight. In the Hebrew Bible, the fig tree is mentioned more frequently than any other fruit-bearing plant. Adam and Eve famously covered themselves with fig leaves after eating from the Tree of Knowledge, making the fig humanity’s first clothing.

The fig tree becomes a symbol of peace and prosperity in numerous Biblical passages. The phrase “everyone under their own vine and fig tree” appears multiple times, representing an ideal state of security and abundance. When King Solomon’s peaceful reign is described, the text notes that “Judah and Israel lived in safety, everyone under their own vine and fig tree.”

The Temptation of Adam and Eve, depicting them wearing fig leaves, from the Kaufmann Mishneh Torah.

In the New Testament, Jesus tells the parable of the barren fig tree and famously curses a fig tree that bore no fruit. He also uses the fig tree as a teaching metaphor, saying “Learn from the fig tree: as soon as its twigs get tender and its leaves come out, you know that summer is near.” The fig’s prominent place in Christian scripture ensured its cultivation spread wherever Christianity went.

Islamic tradition also holds figs in high regard. The Quran includes a surah (chapter) named “At-Tin” (The Fig), which opens with an oath sworn by the fig and the olive. Islamic tradition identifies the fig as one of the fruits of paradise, and the Prophet Muhammad reportedly said, “If I had to mention a fruit that descended from paradise, I would say this is it,” referring to the fig.

In Buddhist tradition, while the sacred Bodhi tree under which Buddha achieved enlightenment is a different species (Ficus religiosa, the sacred fig), it belongs to the same genus. This demonstrates the widespread reverence for Ficus species across multiple religious and philosophical traditions.

Symbolism across cultures

Beyond explicit religious meanings, figs accumulated layers of symbolism across cultures. The fig’s abundance of seeds made it a universal symbol of fertility and prosperity. Mediterranean brides often received figs or fig-related gifts, and fig trees planted at weddings symbolized fruitful marriage.

The fig leaf, of course, became Western art’s standard method of preserving modesty in depictions of the nude human form. During the Victorian era, fig leaves were even added to classical sculptures that had previously been displayed without such additions. The British Museum’s collection of plaster casts reportedly included a removable fig leaf for a cast of Michelangelo’s David, to be attached when Queen Victoria visited.

In ancient dream interpretation texts, figs represented wealth, health, and success. The Greek dream interpreter Artemidorus wrote that dreaming of eating sweet figs meant receiving good news or wealth, while sour figs indicated disputes or illness.

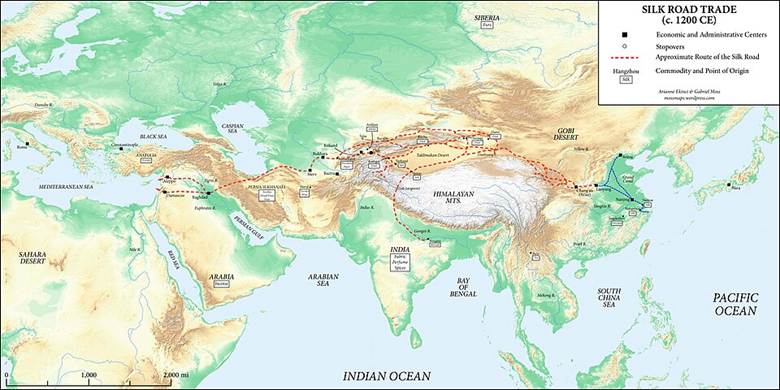

The fig travels the Silk Road

As trade routes expanded, figs traveled along them. The Silk Road carried dried figs eastward into Central Asia and China, where they were prized as exotic delicacies. Chinese medical texts from the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) describe figs as beneficial for digestion and circulation, incorporating this foreign fruit into traditional Chinese medicine.

Silk Road trade map, by Mossmaps, CC-BY-SA 4.0.

Arab traders and the expansion of Islamic empires further spread fig cultivation. By the medieval period, figs were growing throughout North Africa, the Middle East, and into Spain and Portugal under Moorish rule. The Moors developed sophisticated irrigation systems that allowed fig cultivation in semi-arid regions, and they cultivated numerous varieties suited to different climates.

The Spanish mission system would later become the vehicle for spreading figs to the New World. Wherever Spanish missionaries established outposts in Mexico, California, and South America, they planted “mission figs,” a dark purple variety that became one of the most important commercial figs in the Americas.

Mediterranean agriculture and the fig economy

Throughout the Mediterranean basin, figs became a cornerstone of agricultural life. The trees required minimal care once established, thrived in poor soils where other crops struggled, and produced abundant fruit. Dried figs could be stored for months, providing nutrition through winter when fresh produce was scarce.

Greek islands like Crete and Kalymnos developed economies substantially based on dried fig exports. Turkish Smyrna (now Izmir) became famous for its golden Smyrna figs, which were exported worldwide. By the 19th century, the Smyrna region was producing thousands of tons of dried figs annually, shipped in distinctive wooden boxes that became collector’s items.

The fig harvest became a defining cultural moment in many Mediterranean communities. Families would spread figs on rooftops and terraces to dry in the sun, turning and rotating them daily. The drying process required skill to prevent spoilage while achieving the right texture and sweetness. These traditions created a body of knowledge passed down through generations, along with songs, festivals, and rituals centered on the fig harvest.

Figs reach the Americas

Christopher Columbus brought figs to the Americas on his second voyage in 1493. Spanish conquistadors and missionaries continued the work, planting figs throughout Mexico and Central America. By the 1520s, figs were growing in Hispaniola, Cuba, and Mexico.

The real fig revolution in North America came with the California missions. Starting in 1769, Franciscan missionaries planted “Mission” figs at each mission they established along the California coast. The climate proved nearly perfect for fig cultivation, and soon wild descendants of these trees were growing throughout California valleys.

Commercial fig production in California began in earnest in the late 19th century. However, growers attempting to cultivate Smyrna-type figs faced a puzzle. The trees bloomed but the fruit dropped before ripening. After considerable frustration and research, the solution was discovered: these figs required pollination by specific fig wasps that didn’t exist in California.

In 1890, the U.S. Department of Agriculture began importing fig wasps from Turkey. After several failed attempts, a successful population was established in 1899, launching California’s Smyrna fig industry. The Calimyrna fig (a name combining California and Smyrna) became one of California’s premier agricultural products.

The fig in literature and art

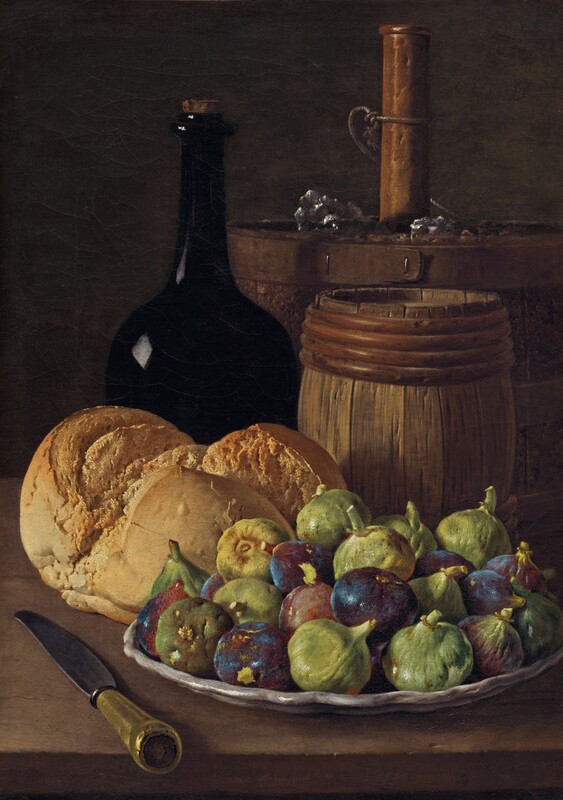

Throughout history, artists and writers have returned again and again to the fig as subject and symbol. Ancient poets praised its sweetness and abundance. Medieval herbals illustrated it carefully, recording its medicinal properties. Renaissance painters included figs in still-life compositions symbolizing abundance and the bounty of creation.

Still Life with Figs and Bread, Luis Meléndez

D.H. Lawrence wrote an entire poem, “Figs,” meditating on the fruit’s symbolic and sensual qualities.

The proper way to eat a fig, in society,

D.H. Lawrence

Is to split it in four, holding it by the stump,

And open it, so that it is a glittering, rosy, moist, honied, heavy-petalled four-petalled flower.

Pablo Neruda included an “Ode to the Fig” in his collection of odes to common things. The fig appears in the works of Shakespeare, Milton, and countless others, its cultural resonance ensuring its literary immortality.

The fig tree’s distinctive large leaves and unique fruiting pattern made it a favorite subject for botanical illustrators. From Maria Sibylla Merian’s detailed 17th-century engravings to modern botanical art, the fig’s visual appeal has inspired detailed scientific and artistic documentation.

A fruit for the ages

From the Jordan Valley 11,400 years ago to modern farmers’ markets around the world, the fig has journeyed alongside humanity. It fed ancient Olympians and Roman senators, symbolized paradise in sacred texts, traveled along trade routes, and helped colonize new continents. It has been payment for labor, offering to gods, medicine for ailments, and simple daily sustenance.

The fig’s story is inseparable from human history because the fig itself is inseparable from human intervention. Those early farmers who noticed and propagated the first seedless fig trees created not just a crop but a partnership that would span millennia and circle the globe. Every fig tree growing today, from California orchards to backyard gardens in Texas, can trace its ancestry back to those first cuttings taken by Neolithic farmers.

As we enjoy fresh figs on a summer afternoon or add dried figs to our morning oatmeal, we’re participating in a tradition older than written history, tasting a fruit that has symbolized everything from wisdom to fertility, peace to prosperity. The fig has witnessed the rise and fall of empires, the birth of religions, the expansion of trade, and the globalization of agriculture.

Frequently asked questions about fig history and culture

Are figs really older than wheat as a cultivated crop?

Yes! The 2006 discovery at Gilgal I in the Jordan Valley found carbonized figs dating to approximately 11,400 years ago, about a thousand years before wheat, barley, and legumes were domesticated. What makes this especially significant is that these were parthenocarpic figs (developing without pollination), a trait that doesn’t occur in wild figs. This means someone intentionally propagated these mutant trees, making fig cultivation possibly the oldest form of agriculture practiced by humans.

How did ancient people cultivate figs without understanding pollination?

Figs were remarkably easy to propagate compared to grain crops. When a farmer noticed a tree producing seedless figs, they could simply cut off a branch and plant it in the ground. Fig cuttings root easily, and the clones would produce the same seedless fruit. No understanding of cross-pollination or complex seed selection was required, just observation and the ability to stick a branch in soil. This simplicity likely contributed to figs being one of humanity’s first crops.

Where does the word “sycophant” come from?

It comes from ancient Athens and literally means “fig-shower”! The Greeks prized their figs so highly that exporting them was illegal. Informers who reported illegal fig exports were called “sycophants,” combining “sykon” (fig) and “phantes” (to show). Over time, the term evolved to mean someone who curries favor through false accusations or flattery, which is the meaning we use today.

Did Cato really use figs to start a war?

According to historical accounts, yes! Roman politician Cato the Elder was determined to convince the Senate to destroy Carthage. In a dramatic gesture, he produced fresh figs in the Senate chamber and announced they had been picked in Carthage just three days earlier, demonstrating how dangerously close Rome’s rival was. Combined with his famous phrase “Carthago delenda est” (Carthage must be destroyed) at the end of every speech, his campaign succeeded in launching the Third Punic War.

Why are figs mentioned so often in religious texts?

Figs appear prominently across multiple religious traditions because they were such a vital part of daily life in the Middle East and Mediterranean. In the Hebrew Bible, fig trees are mentioned more than any other fruit-bearing plant. The phrase “everyone under their own vine and fig tree” symbolized peace and prosperity. In the Quran, there’s an entire chapter named “At-Tin” (The Fig). The fig’s abundance, reliability, and importance to survival made it a natural symbol for divine provision, peace, and abundance.

Were Adam and Eve’s fig leaves historically accurate?

While the Biblical story is theological rather than historical, fig leaves would have been a practical choice in the ancient Middle East where the story is set. Fig trees were ubiquitous, and their large, distinctive leaves would have been immediately recognizable to ancient audiences. The story’s use of fig leaves helped cement the fig’s place in Western culture and art, where fig leaves became the standard way to preserve modesty in depictions of nudity.

How did figs get to California if they need specific wasps?

This was actually a major agricultural puzzle! Spanish missionaries brought “Mission” figs to California starting in 1769, and these common figs grew well without wasps. But when growers tried to cultivate Smyrna-type figs in the late 1800s, the fruit kept dropping before ripening. After considerable research, they realized these figs needed specific fig wasps that didn’t exist in California. The U.S. Department of Agriculture began importing wasps from Turkey in 1890. After several failed attempts, a successful population was established in 1899, launching California’s Calimyrna fig industry.

Why were figs considered training food for ancient Olympic athletes?

Ancient Greeks believed figs built strength and promoted physical development. Greek athletes training for the Olympics consumed figs as a primary training food, and the physician Galen recommended them for building strength. Even Plato was nicknamed “broad-shouldered” partly because he ate many figs, which were thought to promote muscular development. Olympic victors were often presented with figs as part of their prize, cementing the fruit’s association with athletic excellence.

What made Smyrna figs so valuable historically?

Turkish Smyrna figs (from the region around modern Izmir) became world-famous for their golden color, exceptional sweetness, and large size. By the 19th century, the Smyrna region was producing thousands of tons of dried figs annually for export worldwide. They were shipped in distinctive wooden boxes that became collector’s items. The figs’ quality was so renowned that when California successfully grew similar figs, they named them “Calimyrna,” combining California and Smyrna to capitalize on the Turkish variety’s prestigious reputation.

How did dried figs help ancient civilizations survive?

Figs were one of the most reliable preserved foods in ancient times. The trees required minimal care once established, thrived in poor soils, and produced abundant fruit. Dried figs could be stored for months without refrigeration, providing concentrated nutrition through winter when fresh produce was scarce. They were portable, energy-dense, and didn’t spoil easily, making them ideal for traders, travelers, armies, and everyday families. Dried figs were so valuable they were sometimes used as payment for labor.

Why did the Romans care so much about the Ficus Ruminalis?

According to Roman legend, the she-wolf that nursed Romulus and Remus (Rome’s founders) rested under a fig tree called the Ficus Ruminalis. This tree became one of Rome’s most sacred sites, and its health was seen as an omen for the city’s fortunes. When the original tree died, it was considered a grave portent, and Romans would ceremonially plant a replacement. The connection between Rome’s founding myth and this specific fig tree made it a living symbol of Roman identity and destiny.

Are all those old fig trees in Mediterranean villages really that ancient?

While individual fig trees rarely live more than 200 years, the tradition of propagating figs through cuttings means that some fig “lineages” could theoretically trace back thousands of years. More importantly, every cultivated fig tree today can trace its ancestry to those first parthenocarpic mutants propagated by Neolithic farmers 11,400 years ago. The fig trees growing in ancient Mediterranean villages are often centuries-old descendants of trees that were themselves descendants of earlier generations, creating an unbroken chain of cultivation stretching back to humanity’s agricultural beginnings.

Leave a Reply